Leadership lessons from teaching inner city 5th graders

I’ve come to the conclusion that the most effective leadership training bootcamp for Tough Tech CEOs is to teach in an urban middle school. To this day, I think that teaching fifth graders in Philadelphia provided me with some of the most challenging and authentic leadership training out there.

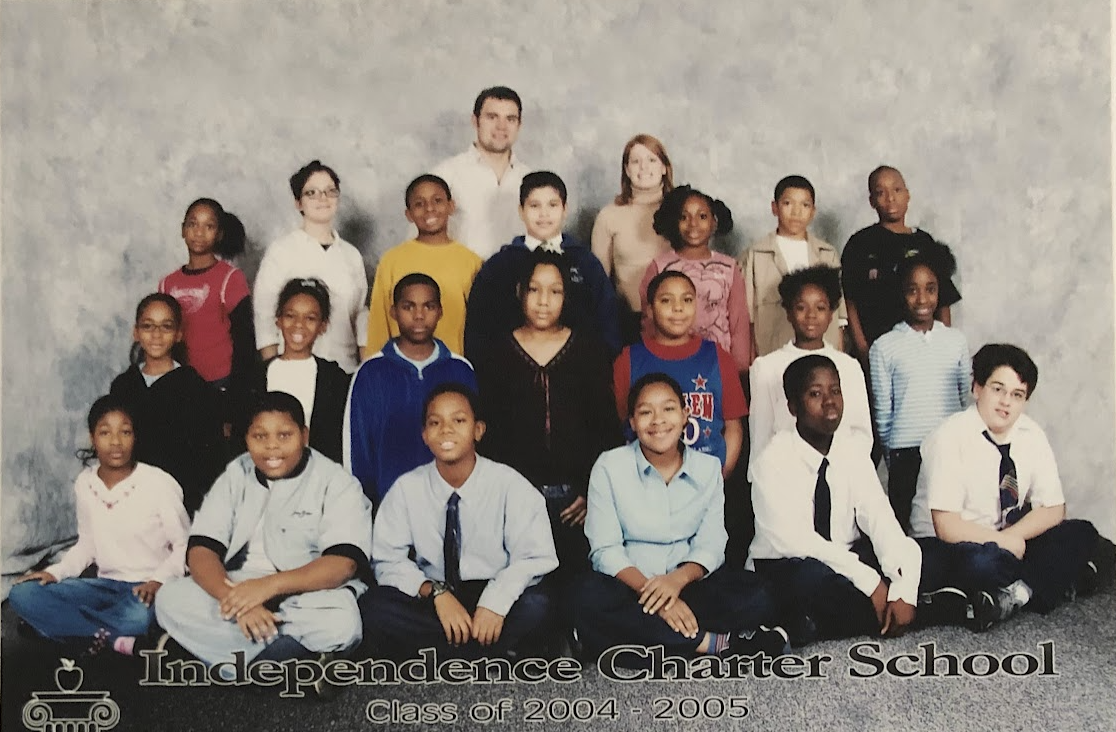

My fifth grade classroom in Philadelphia (the man in the photo was the support team for an autistic child in my room).

While we all demonstrate a blend of leadership approaches and flex different strategies at different moments, we also have a dominant style. I would consider myself to be primarily a “Constructivist Leader.”

I think that the first time I really experienced the power of “constructivist leadership” was when I was teaching fifth grade Language Arts and Social Studies to fifty students at an urban charter school in the heart of Philadelphia. The word “Constructivist” comes from Constructivism, a pedagogical philosophy that means that to deeply learn, we have to construct the knowledge ourselves. We do not passively acquire learning; we have to build it. The same is true of Tough Tech startups. For teams to deeply have accountability and engage passionately in work - we have to authentically construct the organization together.

Teaching at Independence Charter School was my first official job after graduate school. I had two classes of twenty-five students each. The school was located in a renovated office building a few blocks away from the Liberty Bell in Center City. The school was a startup; they added a new grade level every year as their first class of students moved up.

I was given an empty office-turned-classroom that had a whiteboard, tables, chairs, and one PC desktop. That’s it. I had no books, no curriculum, and no classroom supplies. I also didn’t have a budget. I quickly discovered that the fifth graders represented a huge spectrum of learning needs; their reading levels ranged from kindergarten to ninth grade and at least 30% of them had undiagnosed learning disabilities.

I used the Philadelphia teaching standards to provide me with a little bit of guidance on what I was supposed to teach these kids by the end of the year. But I had zero resources to help me figure out how to achieve these learning goals. I was the only teacher teaching this grade and topic, so I was pretty much on my own to figure it out.

At first I tried to design a “literature-based” classroom. I went to a local bookstore and used my own money to buy a bunch of the same book so we could read together in small groups in class. I got nowhere quickly. The kids were totally uninterested; I ended up having endless behavioral problems to manage. I moved the desks around just about every weekend trying new strategies. I experimented rapidly with classroom management approaches. I cried with frustration pretty much every Friday while walking home to my Rittenhouse apartment. I felt like I hit rock bottom when I started wearing a whistle around my neck to school so I could shrill “mercy” when I had to get the classroom’s attention.

I felt like I was failing these kids. They weren’t learning anything at all. I took a pause and decided to take stock in my assets; I start at square one again. I realized that I wasn’t going to get anywhere with them if they didn’t care about what they were learning. I had to build my classroom around harnessing their intrinsic curiosity and motivation. I also realized that the most valuable learning resource I had was to leverage was the city itself, which had a public library nearby and several free historic sites within walking distance of the school.

I decided it was time to “flip” the classroom and let my students drive our curriculum. I asked them: “What have you always wanted to know about our city?” I broke the kids into groups and we made lists and lists of questions for which we’d like to have answers - everything from “How much money does the city make in parking tickets?” to “What’s the most successful business in Philadelphia?”

We grouped the questions and organized them by themes - arts and culture, business, government, etc. The students self-selected into the groups that interested them the most and then they had to figure out how to get legitimate answers from trusted sources.

We used the city of Philadelphia as our classroom. We learned how to conduct research from primary sources at The Liberty Bell, near our school.

To some it might look like I had given up control of the class. But I was in complete control. I was leading from behind. I was creating a structure and environment for the students to push us forward and it was my job was to gather resources, offer structure and support, and help them succeed at achieving their goals. I created a framework and empowered them to dig in and have accountability for their own success.

Sounds a little bit like a Tough Tech startup CEO’s job, right?

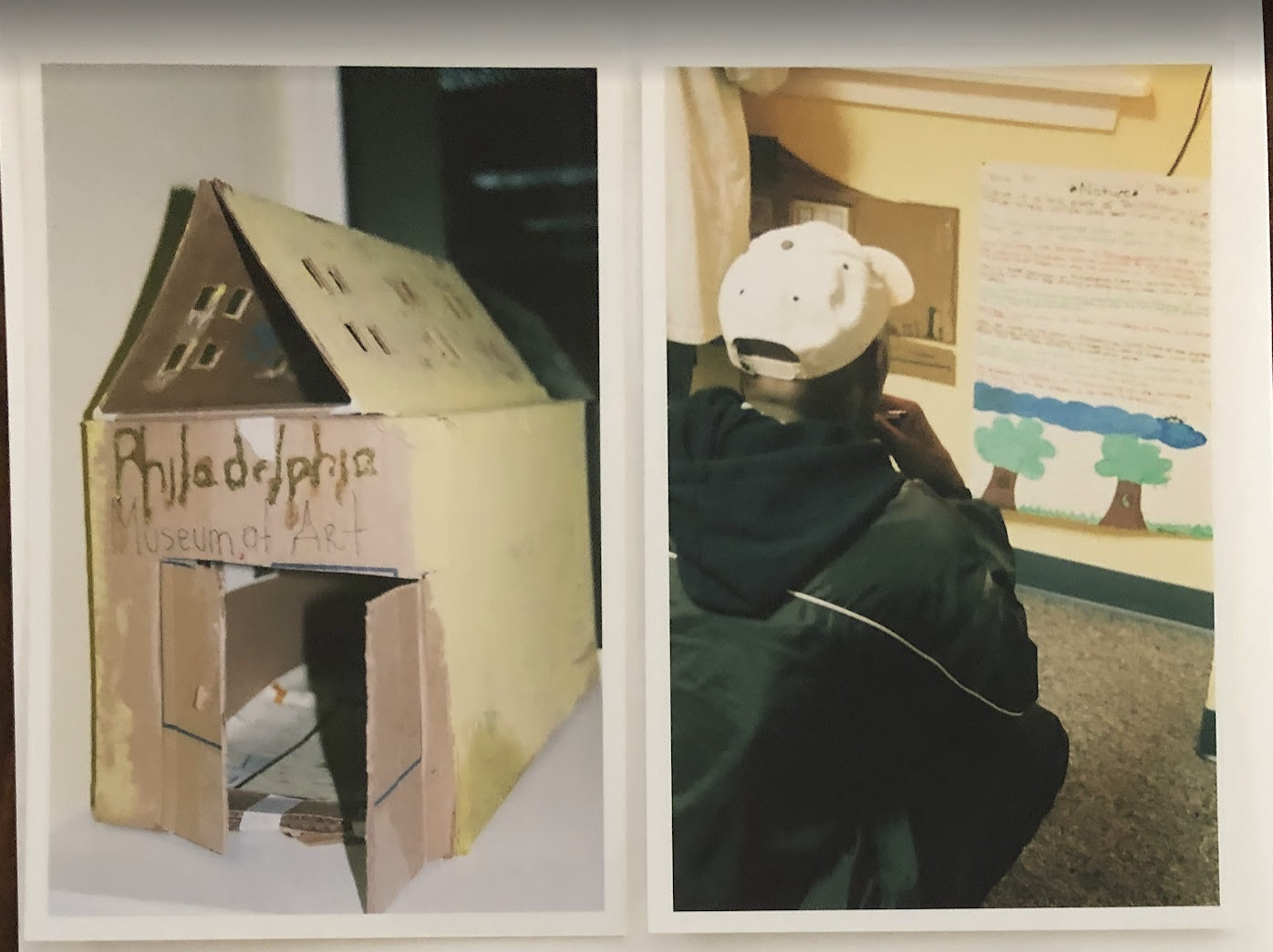

While I was using the students’ own passion and curiosity as the motor for our progress, I was quite sneaky in the way that I wove the educational standards into our daily lessons. I worked my tail off to be a few steps ahead of them so that I would be ready when they came to me with a “just in time” need to learn a new skill or concept. When we’d made some progress on our research, I facilitated a group discussion about how we wanted to share all that we’d learned with our community. We decided to host “Philly 411” - an art gallery showcasing our learnings. We had zero budget but I got the janitors to keep a pile of cardboard boxes for us and we built the most creative stuff. We set up in our school “gym” and sent out invitations.

I’ve got to tell you the coolest metric of success that I discovered from this leadership experiment. Earlier in the year, only four adults came to Back to School night. Four adults for all of my fifty students. But, when we hosted Philly 411, we had over 100+ people show up - including the mayor. (Yes, the kids invited the mayor’s office!) Do you know why those parents showed up? Because their students cared deeply about their work. Those kids dragged their families to come because they were damn proud of how they built their own learning. Those kids constructed the curriculum themselves. I, of course, did a great deal of steering and guiding, but they drove the effort.

“Philly 411” Art Gallery. A parent studying his child’s learning.

As a startup leader, I realized I deploy a very similar approach whenever I lead a team. I want my employees to care so damn much about their work. I want to help each person have radical accountability for their own outcomes and drive success from their own motivations. My job, as the CEO, is to set the stage and make sure all of the actors have their props; I’m the coxswain keeping the team rowing, together, in the right direction.

In many ways, being a “Constructivist” leader is about helping people shine and and providing them with the right environment and structures for them to be successful. To build something extraordinary together, we have to lead others to construct their own journey towards excellence while working towards a shared vision for the future.

I think a lot about how my roots as an educator have shaped the way that I approach Tough Tech leadership. The experience of being an urban middle school teacher taught me how people learn and how to manage people such that they thrive. Although I consider myself an entrepreneur these days, I think I’ll always identify as a teacher at heart.